Instead, Red Cavalry is a singular book with a title perhaps designed to inspire such thoughts — and then, with a twist of the saber, twist your head around.

|

| Red Cavalry poster. |

Babel was a stranger in a strange land. Jewish in anti-Semitic Russia, an intellectual from Odessa, an aspiring writer, and not exactly the physical specimen that made for the ideal horseman. And so, in all their wisdom — or more likely, as a cruel joke — the Russian government sent him to the Russian–Polish front as a correspondent and propagandist for YugRosta (the Russian Telegraph Agency’s southern branch) and embedded him (to use a much more modern term) with the legendary Semyon Budyonny’s Cossack First Cavalry Army. He filed news reports — and kept a diary, which, following his return from the front, he turned into short stories, the first of which was published in 1923. Red Cavalry, or Konarmiya, was published in 1926, revised into a new edition in 1931, and enlarged with additional stories in 1933.

|

| First Russian edition of Konarmiya, 1926. |

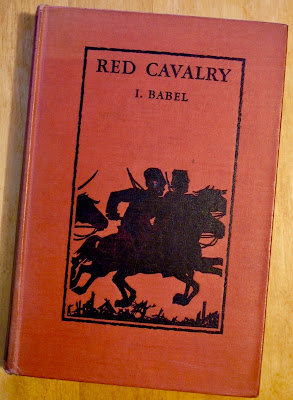

The first English-language edition was published by Alfred Knopf in subtly different versions in New York and London in 1929.

|

| Blood-red covers: First English-language edition, 1929. |

|

| Knopf title page from the American edition. The British edition featured a different design. |

The stories may take you by surprise, both in terms of the lack of heroic daring and the intimate beauty of the descriptive prose. The juxtaposition is startling and stunning.

There are no thunderous cavalry charges, no great victories, no hard-won laurels. Instead, there is destruction, confusion, disarray, horrors, folly, brutality, and characters struggling not to make sense of it all but simply to survive.

And there’s the writing. Babel’s prose mirrors the confusion in its impressionistic style. “An orange sun rolls across the sky like a severed head.” “The moon hung from the sky like a cheap earring.” “Evening laid its palms across my burning forehead. “The scent of yesterday’s blood and dead horses seeps into dusk’s coolness.

|

| Dust jacketed U.S. edition, 1929. |

|

| Spanish-language edition, 1929. |

Ultimately, it’s probably fair to call this an antiwar book. But it’s not so in quite the way of others of the epoch, such as Hemingway’s In Our Time or Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front. There’s no judgment cast on war per se, no attempt to make sense of it all. Instead, Babel’s scenarios and descriptions and characters just are.

It’s easy to see why Gorky — then the most celebrated of Russian writers — hailed Red Cavalry and how Babel was celebrated in the modernist era of Pilnyak and Bely. But why was Stalin himself so staunch an admirer? Did he actually read it? Did he understand it?Or perhaps he savored the horrors that Babel described.

|

| After the fall from grace: Mugshots of Isaac Babel taken by the NKVD after his arrest, circa 1939. He would be shot in Moscow's Butyrka Prison by the Cheka in January 1940. |